Studying the behaviour of consumers in any sector is the norm, but no one has as much data as the television

Tom C. Avendaño

Michael Veale had doubts. It was early January and everyone around him seemed to talk about the same thing, the new success of Netflix: A chapter of Black Mirror, one of its emblematic series, fully interactive. The Spectator controlled the protagonist, a troubled game programmer, and made decisions for him: what cereal to eat in the morning, take LSD or not, talk about his mother with the psychologist. The chapter argument changed every option. “It’s a new kind of narrative that will revolutionate the future,” tweeted Alex de la Iglesia on the opening day.

But Michael Veale, a 26-year-old British who research data protection laws at University College of London, had doubts. “Many people guarantee that the experience was an activity to extract data from users”, says on a visit to Madrid. “I was interested to know not only what Netflix did with all this data, but on what legal basis.” That’s what you asked the house, taking advantage that now these requests for information are supported by the general Data Protection regulation that came into force in Europe last May. “Since we have the right to investigate and understand activities like this, I wanted to show that the regulation can be used to ask questions about everyday issues,” he continues. This week, Netflix gave you the answer. Effectively, he had noted every decision taken by each spectator. The Black Mirror chapter was, for many, a triumph of television creativity; For others, a triumph of data mining.

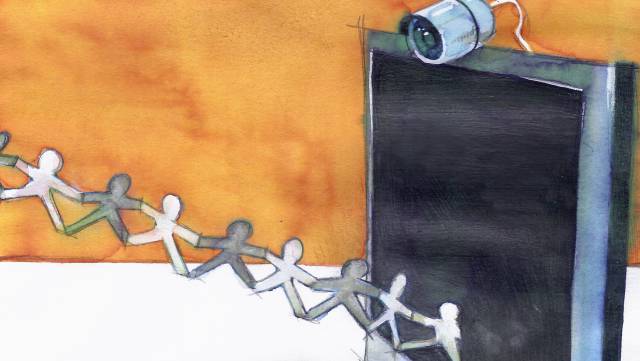

It is also an example of how absurd it is to separate one thing from the other. In a time marked by the mass study of the behaviour of every consumer in any sector, television has become a powerful weapon. The big ones in the business have become what they are today fundamentally by their way of exploring the data that each viewer leaves on a screen connected to the Internet. Every second of yips before choosing a title, each pause in the playback of the program, each scene rewinding. All data contributes to meet the Spectator, and each spectator collaborates to know the entire market. The more banal the dice, the better. More valuable will be crossing it with other millions of variables.

Netflix is the service best known for its way of studying its nearly 150 million subscribers worldwide. But you’re definitely not the only one. When Amazon set out to launch its subscription television business (now Amazon Prime Video), in 2012, it offered a series of pilot chapters for the audience to vote on which they wanted to see transformed into series. At the same time, they determined which chapter was most viewed according to which people, which moments were more rewinding and which had more pauses. With that they made their decisions. Those series would not work.

It was a very different style than Netflix. “They understand the limitations of analyzing data, and know how to overcome them based on human experts,” explains Sebastian Wernicke, director of data analysis at the German consultancy One Logic, who studied the role of big data in television creation. “Netflix does not only decide with data at hand, but uses the data to improve the decisions it takes.” In the house it is said that whenever they produced House of Cards in 2013 it was because they knew that their audience liked political thrillers and films of David Fincher. But they called Fincher. The data informs the creative part and the creatives form the data.

That is why there is still the recurring play in the industry to blame the NETFLIX algorithm for all the coincidences between the House series: The shy dark-haired protagonists passionate about a woman smarter than them (Sex Education, Elite, End of the F In World, 13 Reasons why) or the amount of series whose season is halved by a chapter in a remote place, such as a car trip or a funeral. They must really like the algorithm. They didn’t receive any pauses or rewinding, so there are so many.

“I’m not sure how much more data could be gathered, but if they found them, they would refine the strategy,” Wernicke. Maybe with experiments like the Black Mirror? Here Veale Pondera: “The data collected in this case should concern us? Certainly not. But the fact that they’ve taken more information than the customers allowed by signing, without asking permission? Yes, that data is worrying. ”

Brasil.elpais.com