When Herman Rothman, a German Jew who worked for the UK intelligence Service, was awakened by a phone call in a dawn of 1945, he had no idea what his mission would be. At that moment, he did not know that the British authorities had just arrested a Nazi officer named Heinz Lorenz for using false identification documents. Lorenz was press adviser to the third Reich propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels. When examining his jacket, inside the shoulder pads, the officers found some documents that Adolf Hitler’s personal secretary, Martin Bormann, had asked Lorenz to withdraw from Berlin. They dealt with the testament and the last wish of the Nazi leader. It was up to Rothman and four other men to translate the documents into extreme secrecy, he told reporters when he published his book, Hitler’s Will (the Hitler’s Testament), in 2014. Because they were all Jews, they considered it ironic to be among the first to read what Hitler-who wanted to exterminate them at any cost-had in mind.

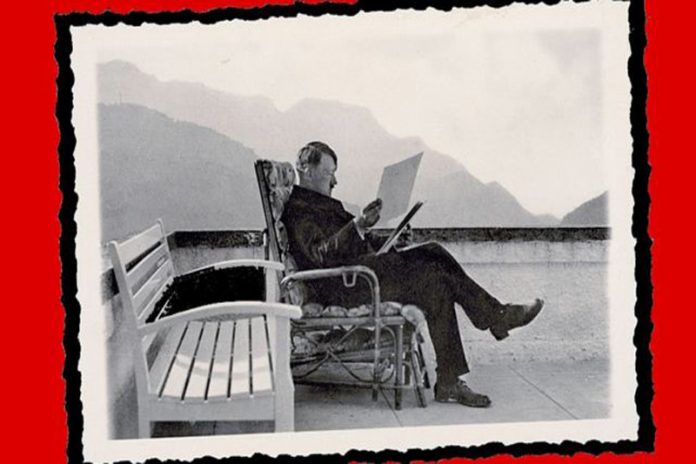

legacy without Fortune? In his last political testament, Hitler exposed his motivations about what he did and what he was still planning to do, all punctuated by expressions of his relentless hatred of the Jews. It also detailed how the government would succeed, in addition to appointing a new office. But in relation to his possessions, there were not many details. “What I possess, belongs to some value-to the party, if this no longer exists, to the state, if the state is also destroyed, no other decision of mine is necessary.” These were the wishes declared by Hitler in another document in which he recorded his last testament, which he dicted and signed in Berlin, along with his political testament, on April 29, 1945, at 4 a.m. sharp. The next day, he killed himself. Collections of painting they had acquired, “were never collected for private purposes, but only for the extension of a gallery in my hometown of Linz, on the Danube,” he said. And his objects of “sentimental value or necessary to lead a simple and modest life” left to his relatives and “faithful colleagues”, as his housekeeper, Anni Winter. It seemed that, at the time of his death, he who commanded Nazi Germany for over a decade had left few material possessions, which coincied with the frugal image he used to promote.

frugal life? The public’s perception was that Hitler did not give much value to money and showed no signs that he lived with ostentation. However, the translators were surprised to discover that the mighty leader seemed to have so little wealth. “We always imagined he had a great fortune,” Rothman said. And they were right. Hitler Long described his poverty and hardship when he was an artist in Vienna before World War I, but accumulated considerable fortune throughout his life. However, it is difficult to accurately estimate your assets.

investigations, documentaries and reports have calculated the amount including or excluding different sources of income, From payments for the use of your image in postage stamps to contributions made by entrepreneurs or corporations. The writer Cris Whetton was one of those who launched this mission, which gave rise to the book Hitler’s Fortune (the Fortune of Hitler), published in 2005. According to him, even obtaining the corrected value of the Reichsmarks (the currency of Germany at the time) in euros or dollars is a difficult task. But Whetton came to a result. “On April 24, 1945 (…), six days before his suicide in Berlin, Adolf Hitler was probably the richest man in Europe, with a fortune of 1.35 billion to 43 billion euros in values of 2003,” he said. The enormous difference between the two sums reflects the difficulty of needing the size of your fortune. But not just that.

The lack of concrete evidence raises another question, about the whereabouts of its wealth, with the more than US $350 Millions found in accounts from an investigation conducted by the United States Intelligence Service, according to documents that came to public decades later. Over the years, information on accounts linked to Hitler has emerged in other countries, such as Switzerland. But it is difficult to trace this money today, because, as it would never have been pleaded, it must have been confiscated by the Swiss government. However, there is some information about the Führer’s finances on which many sources agree.

The publisher published the first 400 pages on July 18, 1925 in a first volume, with the subtitle “Retrospective”. The remainder was published in a second volume, “The National Socialist Movement”, on December 10, 1926. The entire work was republished in a popular edition of a single volume in May 1930.

According to documents found in Munich archives, that year, sales revenues reached 1.2 billion of Reichsmarks, a very high value for the season. To get an idea, a teacher’s annual salary was 4800 Reichsmarks. One of the evidence that Hitler earned a lot of money from the copyright of his book is in the amount of income tax calculated on his income when he was Chancellor of Germany: 405,494 Reichsmarks. The billet was forwarded to the Ministry of Finance, which soon stated: “The Führer does not pay taxes.” The book was translated into 16 languages, which earned him even more dividends, which were administered by Amann, the Nazi Party’s official. Amann became the treasurer of Hitler and remained as director of the publisher Franz Eher Verlag, one of the richest and most influential Nazi Germany, until the fall of the regime. No doubt Mein Kampf made Hitler very wealthy.

“to the party… To the state “after the suicide and defeat of the Nazis, the Allies confiscated Hitler’s heritage. His last will–“what I possess belongs… To the party “-would not be fulfilled, among other more relevant reasons, because, as he himself anticipated-” if this no longer exists, “the Nazi party was abolished. His second option had been “for the state”. But the Nazi state had also ceased to exist. “If the state is also destroyed, no other decision of mine is necessary.” It was the allies who made the decision to transfer Hitler’s property to Bavaria, where the Führer was a registered resident. The house in the mountains was damaged by bombs and looted by the soldiers at the end of the conflict.

in 1952, what remained was destroyed by the Bavarian government to prevent it from becoming a tourist attraction. But Hitler’s old apartment building stood up and started to house a police station. Bavaria took possession of the copyright and prevented the publication of the book in German-speaking territories and, with limited success, elsewhere in the world, until it fell into the public domain on the 70 anniversary of the author’s death on April 30, 2015.